Somewhere Between Spreadsheets and Software

The missing middle

Most people don’t need accounting software, they just need a place to keep their things straight. Over the many, many years I’ve been tracking my savings, I’ve tried every personal finance app under the sun. The category names were cute, the charts were pretty, and every one of them insisted they could “automate my finances.” But automation doesn’t always help. In fact, it often hides the very thing you’re trying to understand: the actual story of where your money goes and why.

When automation gets in the way

Modern finance apps are built for scale, not understanding. They assume you want to optimize for time, for returns, for “insight.” Open any popular budgeting app and you’ll find the same promise: connect your bank account, and we’ll do the rest.

They import your transactions automatically, label them for you with machine learning algorithms, and feed you dashboards meant to summarize your life into green arrows and pie charts. But that’s not understanding.

The fundamental problem with automated finance tools is that they conflate convenience with clarity. Yes, it’s convenient to have transactions imported automatically. But clarity requires something different. It requires you to actually look at each transaction, to make a conscious decision about what it means, to integrate it into your understanding of your financial situation.

Automation promises to save you time, but what it actually does is save you from thinking. And in personal finance, thinking is not a bug to be eliminated. It’s the entire point.

The burden of flexibility

On the other end of the spectrum sits the spreadsheet: beautiful in theory, fragile in practice.

I know this intimately as I’ve been maintaining a personal finance spreadsheet for nearly 20 years. It started simple and elegant, a few columns to track income and expenses along with a summary tab with some basic calculations. But after two decades, it has grown into something else entirely: a sprawling, interconnected web of tabs, formulas, and historical data that I’m now mostly afraid to touch.

The spreadsheet contains the best financial history of my adult life that I have available and while that should feel empowering it instead feels oddly paralyzing. There are formulas in there I wrote 15 years ago that I no longer fully understand or appreciate. There are workarounds built on top of workarounds, special cases accumulated over time to handle situations that seemed temporary but became permanent.

Want to change how I categorize something? I have to trace through multiple tabs to make sure I’m not breaking a calculation somewhere downstream. Need to add a new account? I have to figure out where it fits in a structure that made perfect sense in 2008 but feels arbitrary now.

This is the paradox of spreadsheet freedom. They give you infinite flexibility and zero protection. They can’t tell you when:

A formula drifts or you’ve accidentally introduced an inconsistency

A balance no longer ties out to its component parts

The history of a number disappears into a deleted row

You’ve built a circular reference that makes your entire model unreliable

It’s control without continuity, freedom without safeguards. My 20-year-old spreadsheet is simultaneously my most valuable financial tool and an increasingly unwieldy relic. I depend on it, but I don’t entirely trust it anymore. And the thought of migrating to something else, of somehow extracting and preserving all that history, feels overwhelming.

The spreadsheet hasn’t failed me, exactly. But it has taught me something important: flexibility without structure eventually becomes its own kind of prison.

The missing middle

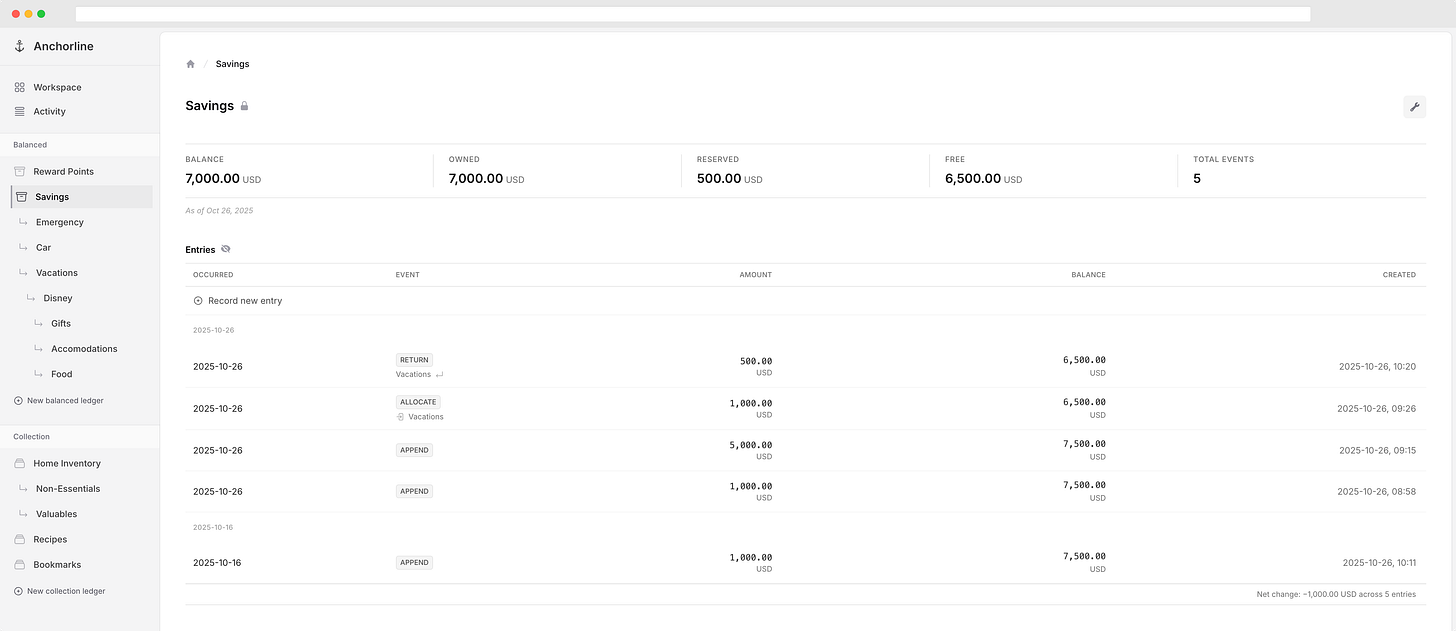

This is where Anchorline comes in, sitting in that uncomfortable gap between structure and freedom, between the rigidity of accounting software and the chaos of spreadsheets. It’s not trying to be either one.

It’s a ledger built around one deceptively simple rule: append, never edit.

Every entry is written once and preserved forever. If something changes, you don’t go back and modify the past. You record the change as a new event, a new line in the ledger. That’s it.

From that single rule comes something remarkable: trust. Because entries are never modified, balances can be replayed from scratch at any point in time. You can ask “what did I have in savings on March 15th?” and get a reliable answer, built up from the immutable history of every deposit and withdrawal.

Collections form clear chains of ownership and meaning. You can see exactly where something came from and where it went. You can track savings, expenses, or projects the same way, consistently and audibly, without needing to wrap your head around double-entry accounting or navigating enterprise software designed for companies with compliance requirements.

The append-only model does something else too: it changes your relationship with mistakes.

In a spreadsheet, a mistake is dangerous. You might have overwritten important data, broken a formula, corrupted your entire system.

In an automated app, you might not even notice a mistake until it’s been compounding for months.

In an append-only ledger, a mistake is just another entry. You see it, you record a correction, and the full history (including the mistake and its fix) remains visible.

There’s no fear, no hidden corruption, just an honest record of what actually happened.

Deliberate systems

Most software tries to save you time, to make things faster and more efficient. Anchorline has a different goal: it tries to give your time structure.

Typing a line into a ledger isn’t busywork that should be automated away. It’s an act of attention, a moment when you pause and acknowledge what’s actually happening with your money. It’s how you stay in touch with where things stand, not through a dashboard or a summary, but through the accumulated practice of recording what matters.

This might sound inefficient to people who’ve been trained to optimize everything. But efficiency isn’t always the right goal. Sometimes what you need is not to move faster, but to move with more awareness.

When you manually enter a transaction, you think about it. You notice patterns you wouldn’t see in an automated feed. You catch errors immediately rather than discovering them months later. You maintain a relationship with your financial reality rather than outsourcing it to an algorithm.

It’s not about optimization. It’s about orientation. Knowing where you stand, how you got there, and what it means. When you can’t erase, when every entry becomes part of a permanent record, you have to think clearly before you write. That constraint isn’t a limitation. It’s a feature that makes you more thoughtful, more deliberate, more engaged with the system you’re building.

Anchorline wasn’t built for accountants who need to prepare financial statements or comply with regulations. It was built for people who like to keep things in order and want that order to last. People who understand that the goal isn’t just to track numbers, but to build a system they can trust six months or six years from now.

People who recognize that the act of maintaining a ledger is not separate from understanding their finances. It is understanding their finances, one deliberate entry at a time.

I plan to get into more specifics for how Anchorline has grown beyond its original finance roots in future posts but I did want to offer this unique perspective on where it sits on the finance spectrum given that was the start for it.

— Lauren